Decolonizing 'Distance Education'?

This past week, I had the privilege of traveling to Athabasca, AB to present on some of my doctoral research to-date at Athabasca University's Education Innovations Research Symposium (EIRS). As part of the day's agenda, we were fortunate to have Dr. Michael Moore, Professor Emeritus of Education at Pennsylvania State University give a presentation first thing in the morning. Dr. Moore was in town to receive an honorary degree from Athabasca University as part of annual convocation ceremonies.

Athabasca University is considered one of the institutional leaders in Canada for online and distance education. I am currently enrolled in the Doctor of Education program offered through their Centre for Distance Education (CDE), with a specialization in online and distance learning. In my research, I have come across Moore's work on a regular basis. I quite appreciate the distinction that he makes between 'distance education' and 'online education'. He argues, and this is highly simplified, that proponents, developers, and scholars of 'online education' should spend a significant amount of time looking to the history of 'distance education' to inform online education.

Moore has worked in the field of 'distance education' (e.g. correspondence courses, radio-delivered education, etc.) since the late 1960s and in various parts of the world including Africa, Canada and the U.K. and worked on projects for the United Nations, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He's even been elected, in 2003, into the US Distance Learning Assoc Hall of Fame. In the mid-80s, he founded the American Journal of Distance Education. Basically, he knows some stuff on this front.

However, I take issue with some of his proposed definitions of 'distance education'. Without trying to be overly provocative, I asked Dr. Moore after his presentation if maybe the current definitions of 'distance education' might be a bit ethnocentric (without actually using that term). I'll try to explain further here.

Moore suggested in his keynote that there is good and open opportunity for a scholar, or doctoral student, to write a book, or dissertation outlining the history of 'distance education' in Canada. He shared some of the work and research he's done providing a history of 'distance education' in the U.S. Some of this includes suggestions that it started in the late 1800s, with potentially the University of Chicago leading the way. He argues that we are approaching a "5th generation" of distance education, or may be in it now. The first generation starting in the 1800s, with subsequent generations including radio-delivered education, then tv-delivered education (of which I remember the "Knowledge Network" and "Open Learning Agency" in B.C. - now part of Thompson Rivers University), and moving into online learning hosted on the Internet.

Since hearing Dr. Moore's response to my question, and returning home, I've looked a little deeper. One of the Moore's main points to my inquiry was that "definitions are important". Thus I turned to some of the literature (again) to see how 'distance education' is defined.

In a significant tome published in 2003 (almost 900 pgs), with Moore and Anderson as editors; Moore suggests in the Preface: "Distance education, which encompasses all forms of learning and teaching in which those who learn and those who teach are for all or most of the time in different locations" (p. ix).

In a 1993 book, Distance Education: A Systems View (Moore and Kearsley), the definition is a simple one: "Students and teachers are separated by distance and sometimes by time" (p. 1).

This is similar to the notions that Dr. Moore offered me when I made my comments and asked a few questions. Of which I will get to momentarily... he did suggest though, that "definitions are important".

In the 2003 Preface, Moore explains his passion behind pulling together the significant synthesis of some of the leading research and thought in Distance Education at the time. This passion, he explains, is based in two of his primary motivations. One, that he has seen far too many researchers and/or doctoral students launch into studies of online learning, which do not account for the near century of previous experience, scholarship, and research regarding 'distance education'. That being, education delivered whereby the teacher and student are not face-to-face, and may be spread across time, or geographic distance (e.g. thus utilizing the postal system for communication, or lessons delivered on TV).

As he argues:

New knowledge cannot be created by people who do not know what is already known, yet what characterizes a great deal of what is presented as research in distance education today consists of data that have no connection with what is already known. In this regard, the enthusiasm for new technology is a problem, because what is known about education at a distance—its organization, philosophies, and issues—are not technologically specific.

People whose starting point is the technology of the Internet cut themselves off from knowing what is known about distance education, for obviously the Internet is so new a communications channel that what is known in that context is minimal.

I fully agree with this notion. Especially as someone that accessed a 'correspondence course' in the late 1980s to complete a required course not offered at the small rural highschool that I attended. (Of course, taking a 'correspondence course' also gave you a 'free' block of time to do other things, as it would be worked into the weekly classroom schedule).

Moore continues:

Beginning with the technology leads to the invention of terms like e-learning and asynchronous [not live, or at the same time] learning, terms that make good sense if one knows the broader context of all that came before the new technology but become serious impediments when they encourage potential researchers to confuse the particular technology (i.e., the species) with the genus of distance education itself.

Again, I am in full agreement. My own professional experience in academic institutions and otherwise is there is a breathless realization that an institution must get it's courses ONLINE. The general assumption is grab the course material - learning objectives, units, text, readings, assignments - and chuck them online. And, PRESTO, the same results will be met and the institution will be viewed as "cutting edge" [see earlier posts on 'bullshit'].

Similarly, Moore points out:

Ask a university professor to design a course for teaching distance learners online and fail to explain, train, or in other ways bring that person to study how courses have been successfully designed for individual learners at a distance using textual communications in hard copy, or fail to introduce that person to the research and experience of building learning communities through audio and video teleconferencing, (not to suggest that the online procedures are identical, but there is knowledge that is transferable), and the result will be a chaos of misdirected, naive, costly, and wasteful initiatives—a fair summary of the state of the art at many institutions today.

This was pointed out in 2003 - yet, these exact events are still occurring almost 15 years later. Both in academic institutions and in other organizations and businesses. Much hoopla is garnered upon Learning Management Systems (LMSs) to close the gap in 'learning' - to create 'learning organizations' and encourage 'lifelong learning'...

Again, Moore:

My experience as a consultant to a wide range of institutions, states, national governments, and international agencies over several decades has led me to conclude that an impatience for moving to action without adequate comprehension of previous experience characterizes not only the research but virtually all ... practice in this field.

In providing an overview for the book, Moore explains how many of the common terms utilized these days (e.g. eLearning, online learning, tele-learning, flexible learning, open learning, etc.) are all related to the 'godfather' term: distance education.

These are all different aspects of distance education, defined as “all forms of education in which all or most of the teaching is conducted in a different space than the learning, with the effect that all or most of the communication between teachers and learners is through a communications technology.” Thus distance education is the generic term, and other terms express subordinate concepts.

Here is the essence of the inquiry/commentary and questions I asked - a bit more detailed now, as I've had time to reflect.

Why is it that 'distance education' is considered to start with academic institutions like Queens University in Canada, and University of Chicago in the U.S.? And, starting in the 1800s?

How is it that we might only be in the "5th generation" of 'distance learning'?

If 'distance learning' is considered, by definition, to be comprised of teaching and learning with the 'teacher' and the 'learner' at different places and/or separated by time - and utilizes some form of 'communications technology' - then:

What is a totem pole? (is it not teacher and learning?)

For myself, having grown up on Haida Gwaii off the northwest coast of BC - there are totem poles carved over one hundred years ago, that served various 'teaching and learning' purposes (e.g. mortuary, house pole, etc.). These poles continue to 'teach' and people continue to learn. The carver(s) (e.g. teachers and learners themselves) have long passed - and yet, the learning provided by them, and the poles, and the places in which they stand (e.g. Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site), continue to 'teach'.

The knowledge(s) that informed the creation of those poles, runs faaarrrr back in time. Teaching and learning over eons.

Is a totem pole, not a 'technology'? Not a form of 'communication technology'? A 'teacher'?

Library and Archives Canada

What is an oral history? (Are these not teachers and learning spread across time and space and place?)

For example, in the well-known and groundbreaking Supreme Court of Canada courtcase Delgamuukw (1997), the Gitsxan hereditary Chiefs presented their adaawk and the Wet'suwet'en hereditary Chiefs presented their kungax. Chief Justice Lamer, at the time recognized these oral histories as 'evidence' within the western-based court system. It was suggested that these constitute acceptable evidence for claim to Aboriginal rights and title, and must be thought of as Aboriginal common law. The testimonies provided by hereditary leaders, of land and resource use and connection to place and space, was acceptable evidence to the courts of physical occupancy.

This case, built upon many previous Supreme Court and lower court decisions, set the context for the Haida and Taku decisions in 2004, and the 2014 Tsilqot'in decision all in the Supreme Court of Canada, which have fundamentally altered the political landscape within BC.

All of these decisions rely on significant impacts of Indigenous oral histories, stories, and protocols. They also go back in time to legislation and policies such as the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

The roots of these stories, as my Settler ears and mind understand - are deeply rooted in 'teaching' and 'learning', and deeper yet, to 'ways of being' and 'ways of knowing'. Yet, my own cultural heritage emanating from Irish and Welsh histories, is also rooted in oral histories. Is that not one of the roots of 'education'?

What is a glacier? (Are these not also teachers and learning spread across time and space and place?)

Anthropologist Dr. Julie Cruikshank has a fascinating book: Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, & Social Imagination. (UBC Press, 2005).

As the book jacket explains:

Do Glaciers Listen? examines conflicting depictions of glaciers to show how natural and social histories are entangled. During late stages of the Little Ice Age, significant geophysical changes coincided with dramatic social upheaval in the Saint Elias Mountains. European visitors brought conceptions of Nature as sublime, as spiritual, or as a resource for human progress. They saw glaciers as inanimate, subject to empirical investigation and measurement. Aboriginal responses were strikingly different. From their perspectives, glaciers were sentient, animate, and quick to respond to human behaviour. In each case, experiences and ideas surrounding glaciers were incorporated into interpretations of social relations.

Focusing on these contrasting views, Julie Cruikshank demonstrates how local knowledge is produced, rather than "discovered," through such encounters, and how oral histories conjoin social and biophysical processes. She traces how divergent views continue to weave through contemporary debates about protected areas, parks and the new World Heritage site that encompasses the area where Alaska, British Columbia, and the Yukon Territory now meet.

Cruikshank explains in her final chapter, which explores the quickly changing terrain and landscapes due to melting glaciers - which includes frozen humans being revealed [Kwäday Dän Ts’ínchi] and all sorts of other materials (e.g. artifacts, ancient furs, etc.).

"Once again, glaciers seem to be playing an active role in negotiating the modern terrain of science, history, and politics in these mountains. Narratives about melting glaciers appear to fall into three interpretive frameworks echoing linked themes that have emerged in this book - environmental change, human encounters, and local knowledge." (p. 248).

...

"For some local residents... the unexpected appearance of tools emerging from glaciers calls attention to older stories. The porosity of boundaries between earth and ice resonate, for instance, with oral traditions we have heard about glaciers that are sometimes solid, sometimes liquid, sometimes dens for giant animals, and sometimes alive themselves. Oral traditions from the Yukon and Alaska depict advancing and waning glaciers as shape-shifters capable of responding sharply to humans." (p. 248).

There is much more to Cruikshank's book that seem very relevant to this discussion - for example, the imposition of boundaries (e.g. 'borders' such as the Canada/US and BC, Yukon borders, the imposition of the UN World Heritage Site in that area, and so on).

Parallel with this, Simon Schama in his book Landscape and Memory (1995) suggests that "landscape is a work of the mind. Its scenery is built up as much from strata of memory as from layers of rock... Landscapes are culture before they are nature."

Cruikshank suggests that in the minds of many, the arrival of Kwäday Dän Ts’ínchi the young man frozen into the glacier (approx. 1400 A.D.) and revealed through melting and receding glaciers was the arrival of a teacher. For example, he confirms oral traditions, and authenticates "the antiquity of travel by ancestors". As Cruikshank suggests "Stories now surrounding his appearance, his contribution to science, his ceremonial cremation, and his return to the glacier where he was found, point to practices [e.g. learning?] crucial to maintain balance in a moral world." (p. 250).

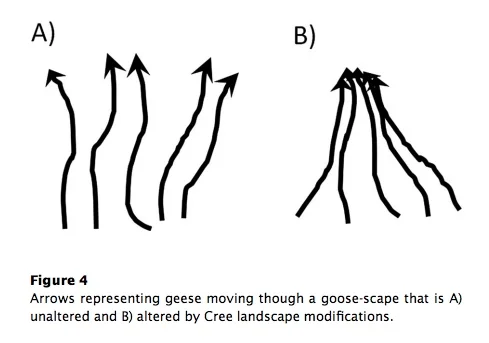

What is a goose-scape?

I recently came across the article: No wilderness to plunder: Process thinking reveals Cree land-use via the goose-scape (Sayles, 2015). As explained in the abstract:

Wemindji Cree [Wemindji, James Bay, Quebec] live in a dynamic coastal setting where land rises up having been weighed down during the last glaciation. Rising land causes plant and animal habitats to shift and with them, prime goose hunting locations. As part of their resource management system, Cree cut large forest corridors, dike wetlands, and are experimenting with prescribed burnings to facilitate hunting geese, an important subsistence and cultural resource.

Sayles explains how hunting geese is a critical component to the communities and families. "Men hunt where their grandfathers hunted before them, where their grandfathers taught them. Hunters also manage these areas... so future generations have places to hunt" (p. 299).

Goose-scape alteration

"Hunting connects people with tradition." (p. 299).

The landscape is changing quite rapidly due to isostasy - rebound of ground-level after the sheer weight of continental glaciers receding. "Cree physically alter their environment to slow changes caused by land uplift. When land rises, wetlands drain and take new form. Upland plants shift seaward. Habitats change. Geese relocate. The land is in perpetual motion."

From Sayles, 2015

As Sayles explains, "To fully understand Cree's intent behind these modifications is to see the world through goose eyes." The fundamental basis of the argument of the paper is not about land-rights per se, however is about 'understanding' land-use and potential implications.

Sayles makes some poignant comments that fit the point I raise here. "Euro-Canadian society has a history of developing indigenous peoples' lands without engaging those peoples as equal partners. One reason for this hegemony is a false preception that those lands were unoccupied and unused wilderness, a perception that partly stems from an inability to recognize lands and resources uses that differ from one's own." Sayles argues for a different 'ontological lens' (e.g. recognizing different ways of being).

The article argues from a 'process thinking' perspective which emphasizes "actions, relations, and transformations and contrasts with dominant worldviews, which focus on objects and static states... Process thinking focuses on movement and connections... Process thinking can help us (re)experience the world and our place in it." (p. 298).

"Movement necessitates time as a medium, which is an essential aspect of process thinking."

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Time is also a medium within 'distance education'. As can be: 'place' and 'space'.

'Decolonizing' suggest some .. is "about the process, in both research and performance, of valuing, reclaiming, and foregrounding Indigenous voices and epistemologies" - e.g. 'ways of knowing'). (Swadener and Matua, in Critical and Indigenous Methodologies, 2008).

They also argue that decolonizing research "uncovers the colonizing tendencies language, specifically the English language, which threatens many indigenous languages with the extinction, the centrality of the US academy in the articulation of 'valid' research questions and processes for investigating those questions..." (p. 31).

Swadener and Matua suggest that "decolonizing research recognizes and works within the belief that non-Western knowledge forms are excluded from or marginalized in research paradigms, and therefore non-Western/Indigenous voices and epistemologies are silenced..." And that research needs to be reframed so as to "actively decenter the Western academy as the exclusive locus of authorizing power that defines research agendas."

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

In 1993, Dr. Moore suggested that a "distance education system consists of all the component processes that make up distance education, including learning, teaching, communication, design, and management, and even such less obvious components as history and institutional philosophy" (p. 5).

What if this was viewed with some of the questions I've raised - learning, teaching, design, communication and management within Indigenous knowledge systems (aka history and 'institutional philosophy')?

What if we looked to Indigenous communities for learning about different ways of knowing and being (e.g. epistemologies and ontologies)? How is it that knowledge(s) essential for living (e.g. living near glaciers and maintaining goose-scapes, ocean currents, moon cycles, etc.) can be passed on for thousands of years? Are these not forms of 'distance education' across time and space? Are these not critical skills for living? - e.g. more important than my distance education course in 1989 on 'Beginner Russian.

What happens when these ocean currents change? Or landscapes change - e.g. disappear underwater due to rising sea levels, or reservoirs due to dams, or land rising above water due to isostasy?

What if we learned from communities how to enact a 'decolonized' approach to teaching and learning, to research - across distance, space and time?

What if we learned to utilize and navigate the online environment informed by decolonized approaches? What might be possible?

_ _ _ _ _ _

My intent here is certainly not to mount criticism; however, more to move the idea of 'knowledge' to a more open place. In the spirit of Dr. Moore's suggestion that: "New knowledge cannot be created by people who do not know what is already known, yet what characterizes a great deal of what is presented as research in distance education today consists of data that have no connection with what is already known."

Sometimes what is defined as 'known' is simply due to lack of experience, cultural blinders, tunnel vision, or deep immersion in one way or another of 'seeing as'.

My own feelings, as a non-Indigenous Settler, is that the field of 'distance education' could do with some significant decolonizing, or at least opening to much expanded viewpoints about what may, or may not, comprise 'distance education' - let alone what might be described as 'education' and whom, or what, might deliver it - and probably more importantly... develop it (e.g. learning, curriculum, etc.)

For example, as a coastal dweller for many of my years, I can tell you the moon delivers much teaching and learning... as does the ocean. Let alone that my understanding is that Dakelh speakers where I currently live in central BC have names for each 'month' based on what the moon brings or affects, be it fish, birds, or other creatures.