the Learning Iceberg - the importance of distinctions between 'education' and 'learning'?

the Learning Iceberg

The Learning Iceberg

As I navigate work in various public sector organizations - healthcare and post-secondary education - and important conversations and initiatives related to Truth and Reconciliation in the geographic area of Canada and cultural safety and cultural humility in public sector organizations - there is much handwringing, debate, and discussion about: knowledge(s), education, training, learning, and the contexts in which these occur, or, ‘should’ occur. During the covid pandemic, there has also been an added debate about online versus face-to-face learning, training, and education (granted this debate was also well underway prior to the pandemic).

There is currently a lot of discussion and initiatives in this country related to the TRC Calls to Action, which have multiple recommendations for education, skills-based training, and learning that needs to, and should occur. I have frequently seen components of the Calls, or reference to specific Calls, worked into many job descriptions and job postings.

Cultural safety is a concept that has come to the forefront in healthcare, especially in BC. This term, and practice, has become more embedded over the past five years. Part of the journey of cultural safety is specific to educational and learning processes and outcomes. It’s actually one of the roots of the term.

Related to this is the concept of cultural humility, which arose out of academia in the United States. Cultural humility is referenced as a journey of lifelong learning.

These two terms are now part of a Declaration, signed by the BC Ministry of Health and all health authorities in BC in 2015. It was endorsed by all 23 health regulators in 2017, and multiple other agencies since. The Declaration is one of the responses to specific anti-Indigenous racism and discrimination in this country, and province.

_ _ _ _ _ _

Through the work of embedding and hardwiring things such as the TRC Calls to Action, and concepts such as cultural safety and humility, I have been rather struck and fascinated in recent years, how little discussion there appears to be on providing distinctions between some of the terms associated with enacting and embedding the knowledge and skills outlined. Many words are taken as a matter-of-fact, for example, BC Health Regulators are suggesting a Cultural Safety and Humility Education Toolkit.

A quick look at dictionary definitions does not necessarily assist. “Education” for example, is listed as the thing that happens at schools, colleges, and universities, as well as, the knowledge, skills or understanding that one gains at these institutions. “Education” is also defined as the discipline in which teaching and learning are studied; one could easily add training.

When one utilizes the sometimes clichéd metaphors of icebergs - as I have chosen to explore here - there are some challenges, some murkiness, some slipperiness, and otherwise that dance around; going in and out of visibility. We can most likely garner some agreement that ‘education’, as a process, engages teaching and accruing or ‘learning’ knowledge. But, what kinds? And, in what contexts? And, how do we know?

I can attest to the credentialing that occurs as an outcome of education - the formal components. However, what are the distinctions between ‘education’ and ‘learning’ and ‘training’?

_ _ _ _ _ _

As shared in my previous post, I recently completed a doctoral degree in education. Prior to that I completed a Masters degree with a focus on ‘adult education’. However, when I reflect upon my ‘formal’ education endeavours, I realize that there is lack of clarity, and sometimes even discussion, about what comprises “learning”. Yet, there are no shortage of individuals, organizations, and initiatives, or buzz-word terms, that suggest learning is occurring, or, is the aim of such-and-such initiative, training, or course - e.g. “learning organizations”, “lifelong learning”, etc.

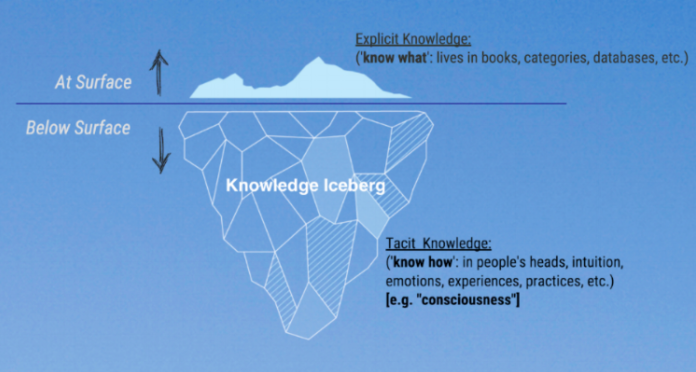

A few years ago I explored the clichéd metaphor of the iceberg in relation to knowledge (see image below). Easily visible and above the surface lies the ‘explicit knowledge’ - the facts and figures; data; the things in books, videos, manuals, emails and otherwise. This is the easy to explain stuff - such as: what do you know about the weather today? “Well.. it’s the north, it’s January, it’s darn cold! My weather app says -22C right now”.

the Knowledge Iceberg

Explicit knowledge is also known as ‘formal’ and ‘codified knowledge’ and it is a very small component of either an individuals’ knowledge, or a society’s knowledge when compared against ‘tacit knowledge’.

“Tacit” essentially means the unspoken stuff. Tacit things can be implied without being said.

“Tacit knowledge” are the things in people’s heads and hearts; like emotions, consciousness, wisdom, spiritual beliefs, experiences, biasses, etc. With ‘tacit knowledge’ people may not even be aware of it; or it may be felt, and not necessarily expressed explicitly.

Often linked with ‘tacit knowledge’ as well as explicit knowledge - is “implicit knowledge”, which was not included in my earlier ‘knowledge iceberg’. “Implicit knowledge” in a simple explanation is the act of taking explicit knowledge and putting it into action. For example, learning to change a tire on a vehicle; fix a flat tire on a bicycle; learning to send an email.

Implicit knowledge exists in that ‘not so easily seen’ zone of a metaphorical iceberg. Sometimes just above the surface; sometimes just below, or, well below the surface and out of sight..

Thus, as shared on the ‘knowledge iceberg’ - explicit knowledge is the know what whereas tacit and implicit knowledge are the know how. The amount of implicit and tacit knowledge are FAR larger than explicit knowledge.

There is also often a connection with the time it takes to accrue each. Explicit knowledge can be gained very quickly; as well as lost quickly. Implicit knowledge can take longer. Tacit knowledge is often gained over a lifetime and can shift with experiences; it is also affected by socialization; by bias; and can be shaped and formed in groups (e.g. families, churches, workplaces, etc.).

Explicit knowledge is also often the focus of specific ‘education’ programs within institutions and organizations - like health and safety training; first aid training; occupational safety, etc. However, the challenge is, that just because an individual participates in an ‘education’ program, does not mean that the intended ‘learning’ occurs. Or, does the learning or knowledge exist very far beyond the end of the training session. It often does not become embedded in individuals.

Learning vs. Education?

Rogers, an educational researcher, provides a fine analogy for highlighting the confused mixing of “learning” and “education” - as they are often utilized interchangeably or synonymously - e.g lifelong learning and lifelong education. However, it is important to distinguish these terms as providing education does not necessarily result in learning. Similarly, providing a ‘learning experience’ or a ‘learning program’ does not necessarily result in the ‘learning’ that was intended. Rogers (2010) provided the analogy of flour and bread.

Bread is made from flour; but not all flour is bread, bread is processed flour. Similarly, all education is learning; but not all learning is education, education is processed, i.e. planned, learning. Learning is much wider than education. (p. 12)

In an academic paper in 2010, two researchers in the UK - one a psychologist (Hodkinson), the other a sociologist (Macleod) - explored their different perspectives on learning, as well as research methods for exploring it. They suggested:

Learning is a conceptual and linguistic construction that is widely used in many societies and cultures, but with very different meanings, which are fiercely contested and partly contradictory…learning is a concept constructed and developed by people to label and thus start to explain some complex processes that are important in our lives. (p. 174)

The Learning Iceberg

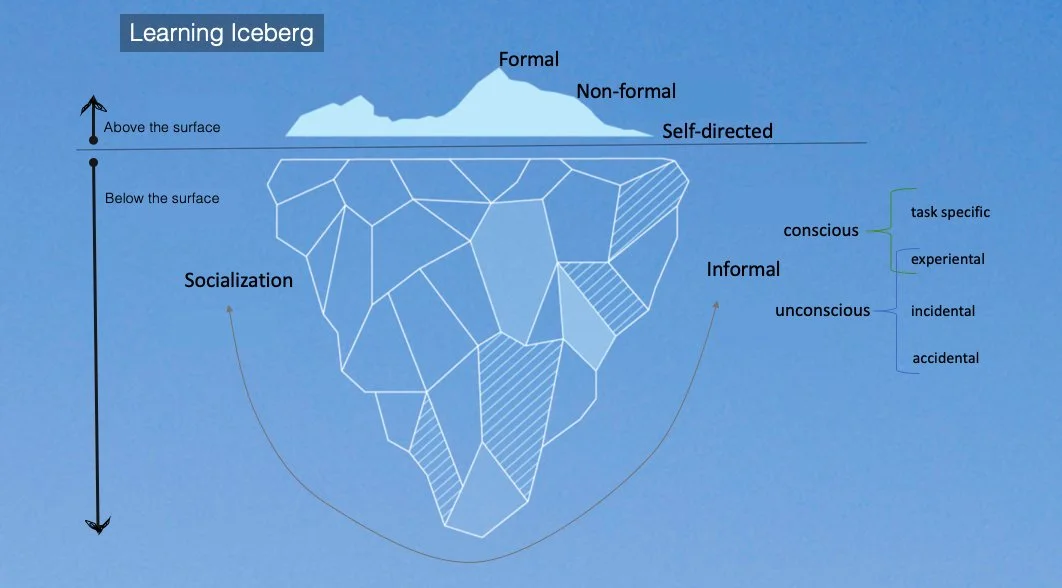

I’ve chosen to explore and highlight “learning” through the metaphor of the iceberg, as this will link to the knowledge iceberg and many others (e.g. culture, systems thinking, etc.). This certainly isn’t unique nor original; however, I’ve found it effective for my exploration and discussion.

Rogers (2010) spurred my pondering on this suggesting:

Informal learning is now recognized as being far more extensive than formal learning. “Most of the learning that people do is informal and carried out without the help of educational institutions” (Williams 1993 p. 23). But it is largely invisible.

The image has been used many times of an iceberg of learning: what cannot be seen is not only larger but also more influential than what can be seen, for it supports and indeed determines what can be seen above the water line.

The most discussed, recognized, and analyzed components of learning, are the formal components - yet, in the whole fuzzy scheme of learning, formal learning is the smallest component including, school-based and institution-based learning and education.

A variety of researchers and institutions have set out to define the terms utilized in the iceberg, including the United Nations and European Union.

Formal learning is one of the easiest to define and recognize, and is located at the very top tip of the iceberg. Formal learning occurs as a result of experiences in an education or training institution, with structured learning objectives, learning time and support which leads to certification. Formal learning is intentional from the learner’s perspective, as well as those providing the training.

Non-formal learning is not provided by an education or training institution and typically does not lead to certification. It is, however, structured (in terms of learning objectives, learning time or learning support). Non-formal learning is intentional from the learner’s perspective. In workplaces, non-formal learning may be represented by the ‘on-the-job’ experience and knowledge gain.

Informal learning results from daily life activities related to work, family or leisure. It is not structured (in terms of learning objectives, learning time or learning support) and typically does not lead to certification. Informal learning may be intentional but in most cases it is non-intentional.

Informal is by far, the largest component of learning - this is the 90% that exists on the iceberg, largely unseen, below the surface. It can include hobbies, spiritual pursuits, general interests, etc.

But because it “takes place below the level of consciousness”, much of this informal learning is not recognised as ‘learning’. “‘Learning’ is seen by many people to be what goes on in a structured programme of intentional learning, i.e. formal learning. But much learning is unconscious, informal”, so we can speak of “the invisible reality of informal learning” (Rogers, 2014, p. 22).

Informal learning is often closely associated with specific activities and tasks, within specific settings, contexts, or purposes. It is often limited, and not generalized. For example, when I learn a new blog platform online, this does not mean I know all blog platforms.

On the iceberg, I’ve also included the link between “informal learning” and “socialization” - these are intimately linked. Rogers (2014):

Even in non-formal learning in the home, much informal learning is going on: “She is learning how to cook, but simultaneously she is also learning gender – she is learning how to be a woman” (Erstad and Sefton-Green, 2013, p 24).

So too for adults: although formal learning often claims academic neutrality, in learning a language or any other subject, for example, we are not just learning decontextualised knowledge and technical skills; through informal learning, we are acquiring a set of values, we are being socialised into a particular culture. This is why informal learning is so important, both for life and also for formal learning. It determines the values, assumptions and expectations we bring to all forms of non-formal and formal learning; it determines our aspirations, our motivations (p. 17).

This is critical to keep in mind when thinking about formal learning, or non-formal learning - it is held up by a wide foundation of socialization and informal learning. These are often where biasses are formed and exist, as well as discriminatory beliefs (both positive and damaging).

_ _ _ _ _ _

Added to the iceberg between informal and non-formal, is self-directed learning.

Self-directed learning can be separated into many distinctions, however, means situations where an individual adopts the identity of ‘learner’ and is largely in control of the learning activities. This could include self-directed online learning, such as an interest in financial investments. This type of learning can include formal components (e.g. Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), books, articles, etc.), non-formal components, and sometimes even informal. Thus, this type of learning could exist across much of the iceberg - visible above the surface and invisible below the surface; mostly below.

Similarly, the majority of learning - the informal learning below the surface - can be split into various distinctions. Rogers (2010) separated these into conscious, task-specific informal learning. These are the sorts of things like learning a new blog platform, or computer program. There is a task-at-hand, and the focus is more on the task, than the ‘learning’ per se. We’re not focussed on the learning outcome; however, a lot of learning may still occur.

This overlaps with the experiential learning that can be conscious and unconscious - yet, still informal. Similarly, this overlaps with both incidental (e.g. advertisements) and accidental learning (e.g. learning from a movie) that can occur in many circumstances, especially when the accidental learning occurs while engaged in a different task. Think for example, of someone inexperienced in sex, watching a movie that has sex in it.

_ _ _ _

Breaking this down.

To bring this back around full circle. Let’s use TRC Call #57 (above) as an example. The TRC recommended that non-Indigenous peoples in Canada (specifically anyone working in government) need to learn about the history of specific things: Indigenous peoples and laws, relationships between Indigenous peoples and the Crown (e.g. governments), aboriginal rights and title, residential schools, and other important topics. Further to this are recommendations on specific skills that need to be learned, or advanced.

The challenge that I ponder quite regularly, is that the Calls to Action (similar to #57) identify the ‘what’; they identify the things, the explicit knowledge.

For example, I can outline to a colleague that I understand that aboriginal rights and title are built upon case law within Canada’s (and other nations) courts - specifically the Supreme Court of Canada. I can explain that the courts have outlined these as collective rights; that the rights are considered sui generis (e.g. unique); and that the case law has been evolving since the 1970s with one of the first cases (Calder). I can outline that Indigenous oral history is now considered evidence in Western-based courts.

These are all largely the ‘what’ components’; the tip of the iceberg.

I can share with someone that I learned the tiniest bit of this within formal learning (explicit); for example, a course at school - certainly not at high school in the 80s and 90s. I have learned a bit more through non-formal learning (e.g. at work and the relationship to healthcare delivery for Indigenous peoples and communities; formation of First Nations Health Authority in BC, etc. ). But, I’ve probably learned the most ‘what’ through self-directed learning, as well as sitting in court hearings, or reading court decisions (e.g. Delgamuukw 1997 and Haida and Taku, 2004).

I’ve learned some informally through community work, or incidentally and experientially.

This gets deeper into “implicit” knowledge area. The non-formal and informal learning begin to delve into the how. After six years working with an Indigenous Health team within a provincially-funded health authority, I learned more about how to apply; and delved more into the WHY. However, a large component of this, is because the WHY is supported by decades of work and self-directed learning in this area. This isn’t intended as congratulatory; nor a suggestion that I have it ‘all figured out’. It’s a reality. I’m still unclear of the ‘how’; other than I recognize there’s a responsibility for someone such as myself; a white settler male carrying privilege.

The reality is that my ‘frames of reference’ were shifted in the non-formal and self-directed learning. Many researchers and commentators use the metaphor of ‘frames of reference’ - largely in relation to socialization. Instilling knowledge and skills are simply not enough for change to occur with most individuals; there must be a change in understanding, and maybe most importantly changes in attitudes and behaviours.

Rogers (2014) proposes the acronym of KUSAB to highlight this. Learning, regardless of whether it is formal, non-formal, self-directed, or informal, must bring about changes in four domains: Knowledge, Understanding, Skills, and Attitudes, which will then result in the ultimate goal of changed Behaviour.

The challenge is that, historically, there has not been a lot of research conducted on the biggest, foundational components of learning: informal learning. Rogers also advocated for a lot more research into informal learning. This is where socialization exists and is embedded; hardwired so to say. Changing the wiring, requires levers exerted across all the domains and across the iceberg of learning.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Thus, some of the more fundamental questions I have, linked with many other questions, are:

How do things need to be structured, pondered, and delivered, for complex items such as the TRC Calls and Cultural Safety and Humility ‘education’? How would these initiatives be evaluated for actual learning? Over what time frames? By what ‘frames of reference’?

How should programs of learning and knowledge-building be structured and delivered, so that they move beyond the ‘tip of the iceberg’ - the WHAT (e.g. facts and figures) - and down into the foundational and structural knowledge of the HOW and WHY? (e.g. the attitudes and behaviours of individuals and groups).

What behaviours specifically are these programs intending to shift within knowledge, understanding, skills, and attitudes? Over what time frames?

Formal learning programs will most likely not result in the desired outcomes, without some deeper thinking that gets further down the iceberg into the 90% below the surface.

The added challenge with formal learning programs, is that they are generally dictated by an ‘authority’ or an ‘agency’. The outcomes are more focussed on what the agency/institution has decided should be the focus. The chance for changes at individual participants’ behaviours is far slimmer. The language irony here may be appropriate - why not more focus on the agency of learners for greater impact, not the agencies wanting to impact the learner.

Approaching some of these challenges through formal programs, is that in many cases, and the TRC clearly identified this, the informal learning of non-Indigenous peoples (e.g. school yard, workplaces, and even formal curriculums) has hardwired perspectives into those individuals’ attitudes and behaviours. Those KUSAB components often did not build respectful understandings of history, or realities, of the foundations of the present-day nation and relationships with Indigenous peoples, communities and nations. For example, one that had peace and friendship treaties in the early days.

Therefore the work to change the knowledge; change the understanding; change the skills and attitudes; and ultimately change the behaviours is much deeper on the iceberg. Below the surface; often deep deep below the surface on the foundational core. Trying to embed skills, or the ‘what’ - through just formal learning - will most likely not change the wiring.

The question that remains here, I find, is: whom is then satisfied with the outcomes? The one that designed the ‘what’ education campaign - or the one that is supposed to learn from the ‘what’ campaign?

And, ultimately, the one that experiences the results of the behaviour and attitude changes, or, lack of changes?

More to come…

_ _ _ _ _ _

* Hodkinson, P., & Macleod, F. (2010). “Contrasting concepts of learning and contrasting research methodologies: affinities and bias.” British Educational Research Journal, 36(2), 173-189.

Rogers, A. (2014). “The base of the iceberg: Informal learning and its impact on formal and non-formal learning.” Verlag Barbara Budrich. Available online.