Reconciling behaviour change?

Systems thinking iceberg

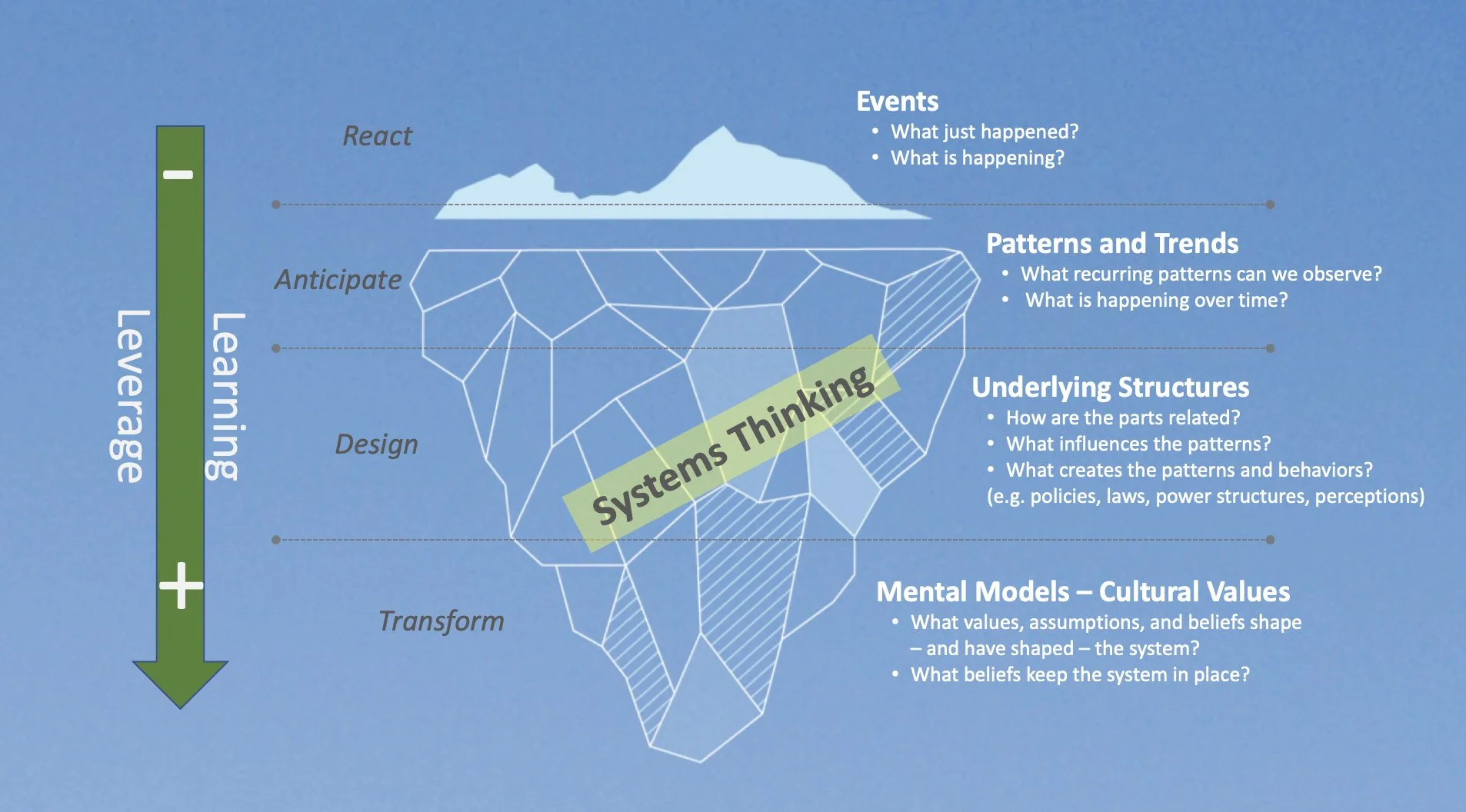

My last post explored some dimensions and distinctions of education and learning. This post continues that exploration, and in relation to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Canada and ongoing work focussed on anti-racism, the ideas of ‘truth’ and ‘reconciliation’, cultural safety and respect along with much discussion and debate about how to enact, embed, and realize principles of compassion, safety, understanding, and ultimately, bigger goals of reconciling past and current relationships. This post continues some reflection and pondering, supported by the continued use of the iceberg metaphor. In this case, using an iceberg to contemplate systems thinking and systems change.

Over the past couple years the globe and human populations have navigated the C-19 pandemic. More recently, many countries are navigating the pushback from public groups, tired of public health measures. Maybe lost in some of these debates, are the different philosophical approaches of public health measures, and individual health measures. Inherent in the approach of public health measures and approaches, are ways of being and thinking that are intended to try to protect the most people possible, with the least amount of intrusion.

This means some are impacted more than others. Think for example back to the early days of the pandemic and debates about limited ventilators and other life-saving equipment. Public health was guiding decisions that were triage - assigning degrees of urgency to certain priority populations. In some cases this meant elderly patents with c-19 would be foregone for younger patients needing the same ventilation equipment to stay alive.

Public health measures through the pandemic have also intended to motivate individuals to enact personal actions that would benefit the apparent greater good - e.g. isolation, social distancing, masks, hand washing, etc. Behind these public health measures were all forms of education and learning. In two years, more people around the world have learned intense amounts of info about the differences between epidemics and pandemics, airborne pathogens, virus mutations, and vaccination. The battles waged on social media and other media channels to try to get the ‘best’ and ‘most relevant’ information out to the masses, and combat the potential misinformation of non-professionals spreading like viruses across social media channels. These continue.

In more recent years, the ideas of racism, anti-racism, discrimination, and other social illnesses have become more embedded in discussions of public health, and healthcare in general. Think for example in BC, of the In Plain Sight investigation and report led out by Dr. Mary-Ellen Turpel Lafonde; the sub-title: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in BC Health Care. Reading through the Findings points to a systems-view.

Findings #1 to #5 outline: The Problem of Indigenous-specific Racism in B.C. Health Care. This section focusses on the top sections of the systems iceberg: what is happening, has happened, and continues to occur (the patterns).

Finding #1 of the report: “Widespread Indigenous-specific stereotyping, racism and discrimination exist in the B.C. health care system.”

Along with Finding #5: “Indigenous health care workers face racism and discrimination in their work environments.”

Findings #6 to #11 focus on: Examining current ‘solutions’. This section discusses “change levers” and the importance of education and training. These components move deeper on the iceberg.

As the green arrow on the left of the diagram at the beginning of this post demonstrates: the deeper we move down the iceberg, the deeper the learning must be, as well as, more leverage is gained to enact and embed change.

Finding #6: “Current education and training programs are inadequate to address Indigenous-specific racism in health care.”

Finding #9: “There is insufficient hard-wiring of Indigenous cultural safety throughout the B.C. health care system.”

These speak to the Underlying Structures deeper on the iceberg, and the Mental and Cultural Models that keep systems in place. Various components of the other Findings in the report outline the many levers of change that need to be operating simultaneously, as well as education, training and learning. Maybe most importantly are the feedback loops that are also required through monitoring and evaluation:

Finding #11: “There is no accountability for eliminating all forms of Indigenous-specific racism in the B.C. health care system, including complaints, system-wide data, quality improvement and assurance, and monitoring of progress.”

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The concept of Racism is contested; as it’s considered an event, and, a process. It can also different in its forms and impacts across diffrent geographic areas. Racism is also considered by Came and Griffith (2018) as a “wicked problem”.

In their 2018 paper, Came and Griffith outline their definitions of racism, building on other researchers explorations - and fitting well with the systems theory iceberg model:

“Racism has been defined as “an organized system, rooted in an ideology of inferiority that categorizes, ranks, and differentially allocates societal resources to human population groups” (Williams and Rucker, 2000). Consequently, racism is an analytic tool to explain systems, patterns and outcomes that vary by population groups that are broader than the explicit decisions and practices of individuals, organizations or institutions.

Beyond a series of isolated incidents or acts, racism is a deeply ingrained aspect of life that reflects norms and practices that are often perceived as ordinary, constant and chronic (Ford and Airhihenbuwa, 2010). Racism is a violent system of power that can be active and explicit, passive and implicit, or between this binary (Young and Marion, 1990).

Racism pervades national cultures via institutional structures, as well as the ideological beliefs and everyday actions of people. While cultural narratives and media coverage often present it as reflecting aberrant views of a minority of people, racism is often aligned with the normative culture of particular eras, geographic contexts and locales ( Griffith et al. 2010; Wetherell and Potter, 1992).”

These two researchers, one based in the U.S. and one in New Zealand, outline that anti-racism “is an educational and organizing framework that seeks to confront, eradicate and/or ameliorate racism and privilege.” They outline further:

“While interventions to undo, eliminate or ameliorate the effects of racism have existed as long as people have faced racial oppression (Fredrickson, 2011), how to educate and organize people to achieve health equity in the context of racism is less well developed (Ford and Airhihenbuwa, 2010; Thomas et al., 2011). Often, anti-racism seeks to heal, organize and empower the oppressed, not those who are advantaged by racism and privilege.”

The reality is that it takes multiple levers and approaches. If we flipped the iceberg above and started with an analysis of the Mental and Cultural Models that hold discrimination and racism in place, we could then move towards dismantling some of the Underlying Structures (e.g. patterns and behaviours).

To get at behaviours, would require strategies of behavioural change. Ask public health experts how difficult this can be for things such as anti-smoking campaigns and healthy eating, or pandemic measures.

Shifting the Underlying Structures, would then facilitate shifting Patterns and Trends. For example, the In Plain Sight report clearly identified commonly experienced patterns and trends within the BC healthcare system (which would then carry over into educational systems, as these are what prepare individuals to work in health care settings).

With a shift in Patterns and Trends, the observed Events (at the tip of the iceberg, above the surface) would change. In the case of racism and discrimination, this would be evaluated by, provided by, and reported by those that experience discrimination and racism. This is the underlying principle of Cultural Safety, as well as the concept of respect.

At the root of much of this Systems Change, is Transformation, which means getting at things deep under the surface - the mental models, values, and beliefs. Behaviours are held up by these foundational elements, which are also often unconsciously embedded (see previous post). These foundational elements are ingrained through socialization (including families, friends, and education). To get at these will take thoughtful Design.

The greatest changes will occur when the largest levers are pulled on - as per the iceberg diagram above. Similarly, to get at those transformational changes takes the largest amount of education and learning. Much of the training and education I’ve come across to date tends to suggest that learning about other cultures and ways of being will shift the mental models that hold systems of discrimination in place.

These types of educational endeavours are important - critical even. However, these most likely only get slightly below the surface.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Returning back to the philosophy and approach of public health - many of the approaches and public health measures through the C-19 pandemic appealed to individual and public behaviours. This required significant behavioural changes and interventions in short periods of time including: isolation and social distancing such as working from home, limiting gatherings of people, physical distancing, wearing masks, washing hands, getting vaccines, etc.

More research is sure to come out on how public health measures and interventions - which can include combatting discrimination and racism - need to look to support behavioural change on a large scale.

I am no public health expert, nor an expert on behavioural change research; however, there are some foundational aspects of behavioural change research, which may increase effectiveness of educational initiatives focussed on combatting negative discrimination and racism. A 2020 article in Nature by West and colleagues explores the relationship between the C-19 pandemic and behavioural change initiatives.

The COM-B model is one model for behavioural change and was developed by by Susan Michie, Maartje van Stralen, and Robert West in 2011 - (see image below from The Decision Lab).

COM-B model for behavioural change

Designing behavioural change interventions is challenging and multi-faceted work. The COM-B model suggests that:

“Understanding factors that influence behavior are the key to behavior change. The COM-B model of behavior change proposes that to engage in a behaviour (B) at any given moment, a person must be physically and psychologically capable (C) and have the opportunity (O) to exhibit the behavior, as well as the want or need to demonstrate the behaviour at that moment (M). This model is effective because it identifies what component of behavior needs to be changed in order for an intervention to be successful.”

The Decision Labs post further defines each component:

Capability in the context of COM-B refers to whether we have the knowledge, skills and abilities to engage in a behavior. This capability comprises mental state, knowledge and skills, and physical strength. For example, to make an individual feel capable of performing a behavior or achieving an outcome, implementing a training session to help support learning of that behavior may boost feelings of capability.

Opportunity in the context of COM-B refers to external factors that make execution of a behavior possible. Physical opportunity, opportunities provided by the environment, and social opportunity are all valid components. For example, to improve the opportunity to begin performing a behavior like regular exercise, free training classes may help.

Motivation in the context of COM-B refers to the internal processes that influence decision making and behavior. Reflective motivation - the reflective process involved in making plans -and automatic motivation -the automatic processes such as impulses and inhibition - are the two main components. For example, to improve motivation, it his helpful to turn a desired behavior from something they need to do, to something they want to do, by encouraging reflection of the benefits of performing that behavior.

Reading through each of these points to the potential limitations of ‘mandatory training’ - think of the various ‘equity’ and ‘diversity’ training initiatives implemented by various organizations. These are also the more ‘formal’ training initiatives - see previous post.

An individual’s behaviour will most likely change if the above interventions are successfully implemented in an environment that is as supportive as possible. This also requires systems changes occurring around individuals (e.g policies, practice, etc.)

Through the changes in many individuals, an institution, a community, a geographic area, will also make and create change.

More to come…